A new international study estimates that from January 1, 2020, to May, 1, 2022, nearly 8 million kids age 18 and under lost a parent or primary caregiver to a pandemic-related cause. When the researchers included the deaths of secondary caregivers like grandparents or other older relatives, the number of kids affected rose to 10.5 million.

That's a big jump from the prior estimate of 5.2 million children who lost a parent or caregiver to COVID-19 from the start of the pandemic until Oct 31, 2021.

The findings are "heartbreaking and disturbing," says Susan Hillis, the main author of the new study, and a co-chair of the Global Reference Group on Children Affected by COVID-19 and Crisis, an international team that's been tracking the indirect toll of the pandemic on children.

Some nations are beginning to address these catastrophic losses with new programs that offer support to the bereaved families – although the U.S. lags in this effort.

Why have estimates gone up?

Asked why the numbers are far higher than previously thought, Hillis answers: "Part of the increases are because we just have more accurate death data on which to model our estimates. And of course, the other aspect of the increases is that deaths have continued."

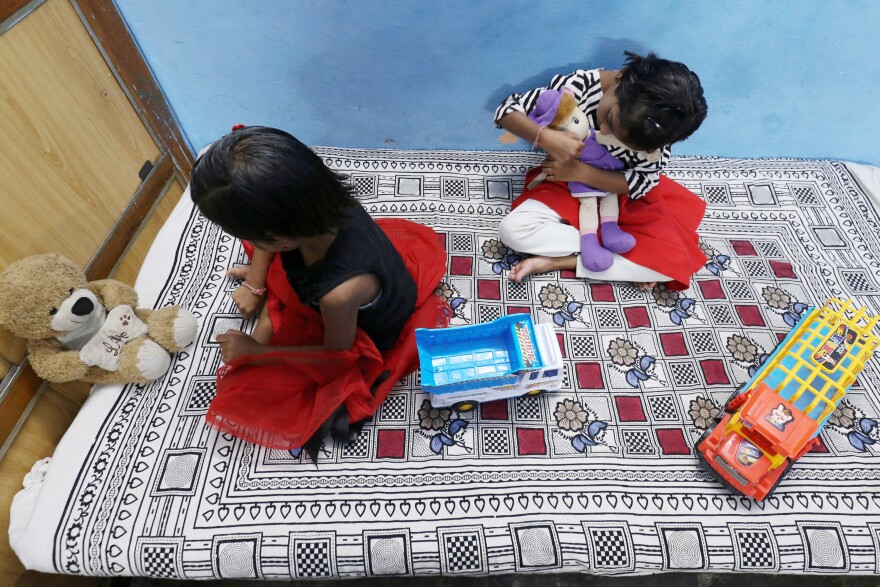

The study, published in JAMA Pediatrics, also found that the greatest numbers of kids affected by these losses were in Africa and Southeast Asia. India has seen the most suffering, with 3.5 million children grieving the loss of a parent or primary/secondary caregiver. However, Bolivia and Peru have the highest rates of kids affected, with 1 out of every 50 children in both countries losing caregivers during the pandemic.

These children face potentially devastating consequences. The emotional toll may be what people think of first but the impact hits many areas of a child's life.

"This enormous bereavement is an economic loss," explains Lorraine Sherr, a psychologist at the University College London, and a member of the Global Reference Group, who wasn't involved in the latest estimates.

That's especially true when the parent or primary caregiver who died was the main breadwinner in the family. A family's loss of income can put kids at a higher risk of food and housing insecurity.

If a child moves to a new community or family because of the death of a parent, "it's a separation," she says. "And then there's disengagement at school and then disengagement with friendships, with things previously that made them happy or helped them learn. So you have this kind of huge cascade of losses."

Bereavement is one of the top predictors of poor outcomes at school, says psychologist Julie Kaplow, executive vice president of trauma and grief programs at the Meadows Mental Health Policy Institute.

Studies also point to the lasting mental and physical health impacts from losing a parent or caregiver.

"It increases the risk of mental health problems, suicide, prolonged grief complications, sexual exploitation and abuse, even physical abuse of children," says Hillis.

Finding ways to help bereaved children

Many countries and organizations are finally recognizing the urgent need to help children and families deal with this loss, says Sherr.

"Some efforts are being put in place, especially in South Africa, in Eswatini and Kenya and Botswana," says Joel-Pascal Ntwali N'konzi, a co-author of the new study and a researcher at the African Institute for Mathematical Sciences in Kigali, Rwanda. In South Africa and Eswatini, 1 in 100 children have lost a parent or caregiver.

Sometimes the solution is in the form of cash aid.

Providing cash payments to such families can ensure that families can afford school fees in countries where education comes with a price tag. N'konzi and his co-authors are hopeful that other countries will join these efforts.

The World Bank is also looking into providing countries with funding for "cash plus care initiative," says Sherr.

"That means that you provide the family with a stipend or a small cash injection, but you twin that with care — some kind of social support services, linking to school and education."

These kinds of support programs would also connect bereaved families with grassroots organizations or nonprofits that can provide mental health care and psychological support to children and the surviving parent or caregivers.

Past research on children orphaned by the HIV-AIDS epidemic shows that such efforts can buffer the impact of the trauma on kids, says Sherr, who has done research on this topic.

"We looked at educational risk, things like missing school, dropping school year achievement," she explains. "We looked at emotional outcomes such as depression, stress, identity, anxiety, trauma. We also looked at positive outcomes like coping and resilience."

She says projects that included cash transfer plus connection to community-based supports and services improved these outcomes among grieving children.

However, there have been no federal efforts to address the crisis here in the United States, notes Rachel Kidman, a social epidemiologist who has studied the long-term impacts of the HIV-AIDS epidemic on children. The new study found that more than 250,000 American children had lost a parent or caregiver due to the pandemic as of May 1, 2022.

And yet, says Kidman, who was not involved in the new research: "I'm not seeing any concerted efforts or even a lead by the federal government" to address the needs of these children."

This story was supported by a fellowship from the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma at Columbia Journalism School.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.